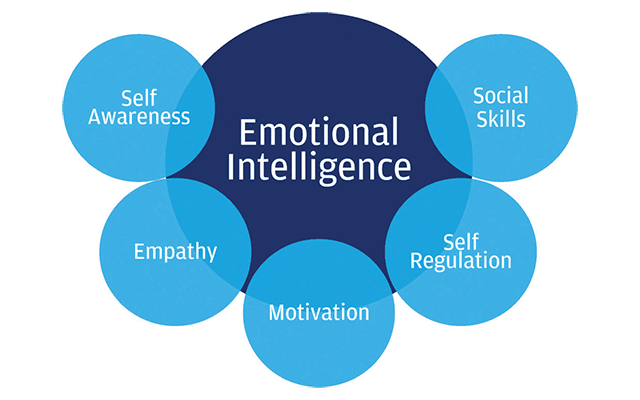

Five key elements, identified in 1995 by American psychologist Daniel Goleman, define emotional intelligence (EI):

- Self-awareness.

- Self-regulation.

- Motivation.

- Empathy.

- Social skills.

EI is the capacity to be aware of, to control and express one’s emotions, and to handle interpersonal relationships judiciously and empathetically. Simply put, people with a high degree of EI know what they’re feeling, what their emotions mean, and how these emotions can affect other people.

EI is the key to personal and professional success. After all, who is more likely to succeed: a leader who shouts at their team when under stress, or a leader who stays in control and calmly assesses the situation?

The more that you manage each of these areas the higher your EI becomes. In fact, it has been argued that EI is more important than the intelligence quotient (IQ) in the development of successful leaders and, by definition, effective managers.

So, let’s review a story and examine how the outcome may have been different.

Brad's story

Brad, an experienced manager of more than 25 years at one of Victoria’s major metropolitan quarries, received a brief email on Monday morning from his boss instructing him to attend a two-day workshop on the upcoming Thursday and Friday at the company’s head office in Sydney.

Brad’s mind raced with questions: “What is it all about? Why do I need to be there? Don’t they know that I’ve got production problems and I’m nursing a ‘sick’ crusher? Who could organise the weekend’s repairs and maintenance schedule while I’m in Sydney? How can I be away for two days when there’s no one capable of standing in for me? And, as well as all that, we’re going through a high demand period at present with the weather threatening to change! It’s typical – they don’t understand what it’s like to manage an operation like this!”

Brad’s boss John, a successful, emerging executive, had been asked a month earlier by the company’s national operations manager in Sydney to nominate an experienced quarry manager, with a passion for product quality and customer service, to join a cross-functional team meeting focused on enhancing the customer experience – or “CX”, a new initiative and directive from the company’s executive management team.

There was just one problem – John had forgotten to make the arrangements for a suitable person to attend the workshop! So Brad was suddenly advised that he must attend the event and to make all necessary arrangements for his team to cover his absence for two days.

Once at the workshop, Brad quickly displayed a poor attitude, with arms crossed, rolling eyes, facial expressions and low sighs. While initially offering no comments, as the discussions progressed and the group raised a number of ideas, Brad suddenly launched into a tirade about how their latest suggestion had failed dramatically in the past and would have no chance of success moving forward!

Both the group and workshop facilitator were confused because Brad had been represented as a champion of quality control and customer service. They had expected constructive ideas and positive feedback from this experienced quarry manager. The interstate quarry managers within the group also held Brad in some esteem but, as a result of his behaviour, they now felt that he had let them down. Brad had potentially damaged the meeting’s operational input – and they were annoyed.

Little did the group appreciate how Brad felt. He had been given no idea about the anticipated outcome of the workshop, how it was to be to be facilitated, where he fitted in, and who else would be involved. He felt that he had no time to prepare and, as a result, he felt vulnerable and more than a little frustrated by the lack of understanding and poor communication from his boss.

Learning vs Competency

In today’s complex, demanding workplace environment, a high IQ doesn’t necessarily equate to being successful. Managers, team leaders and employees need to learn the skills of self-management, interpersonal awareness and effective communication. They need to work positively with each other, discussing topics openly, listening to issues and responding constructively, while effectively managing different opinions and the potential for conflict – all of which will motivate others to operate at a higher level.

Learning these skills is relatively straightforward but gaining competency in applying them requires the development and strengthening of EI. Emotional intelligence is often defined by the way in which emotions are managed in the workplace.

EI is about understanding your emotions and the emotions of those around you; it’s about knowing yourself and your feelings so well that you can manage them effectively at any moment and for any given situation. This means working well under stress, handling working relationships in a personal, yet professional manner, keeping a level head and appreciating the emotional needs of yourself and others.

These key skills can be acquired through mastery of the following:

- Self-awareness – The recognition of your own strengths and weaknesses coupled with the ability to be conscious and understanding of your emotions and to recognise their impact on others.

- Self-regulation – The ability to manage your emotions in a healthy way (self-control). It is about expressing those emotions in a useful, appropriate manner.

- Motivation – Being driven internally, rather than just working for a pay cheque, taking initiatives and adapting to changing circumstances and environments.

- Empathy – The ability to inspire, influence and connect with others (leadership), work well in teams, manage conflict and note/respond to other people’s motivations and needs.

- People skills – The ability to understand other people’s emotions, needs and concerns, pick up on emotional cues, feel comfortable socially, recognise the power dynamics in a group or organisation, to win others’ respect and build rapport.

Following are examples of EI and how their application could have assisted John and Brad:

- Being able to put yourself in someone else’s shoes. A key aspect of EI is being able to think about and empathise with others’ feelings. People who have strong EI can consider the perspectives, experiences and emotions of others and use this information to explain why those people may behave the way that they do.

- Considering a situation before reacting. People who apply EI know that emotions can be powerful – but also temporary. For example, when a team member becomes angry with another co-worker or the “situation” within the workplace, the emotionally intelligent response would be to take some time before responding. This allows everyone to calm their feelings, moderate their responses and think more rationally about what may, or may not, have been “responsible” for the highly charged and emotional outburst.

- Being aware of one’s own emotions. Emotionally intelligent people are not only good at thinking about how other people might feel, they are also adept at understanding their own feelings. Self-awareness allows people to consider the many different factors that contribute to their emotions and those of others.

To that end, EI is important not only for maintaining and strengthening relationships within the company hierarchy but in fostering a collective culture of good will, co-operation and a common motivation for success.

Image courtesy of the Cognitive Institute, cognitiveinstitute.org